When people ask how to calculate site load, they usually expect a formula.

In reality, site load calculation is not about math. It’s about understanding how a site actually behaves electrically when things start, stop, and fail.

I’ve been involved in enough generator sizing projects to say this clearly: most site load calculations fail not because the numbers are wrong, but because the assumptions are wrong.

Before talking about generators, transformers, or utility capacity, I always start by clarifying what site load really means.

What “Site Load” Actually Means in Practice

There are three different numbers that often get mixed together.

Connected load is simply the sum of all installed equipment nameplate ratings. It looks impressive on paper, but it almost never reflects reality.

Operating load is what the site draws during normal operation, after everything is running and stabilized.

Design load is the one that matters.

It represents the maximum credible electrical stress the system will experience, including motor starting, load overlap, and short-term transients.

In real projects, generators fail not because the connected load was underestimated, but because the design load was misunderstood.

Step 1: Build a Realistic Load List, Not a Perfect One

I don’t start with software. I start with a simple list.

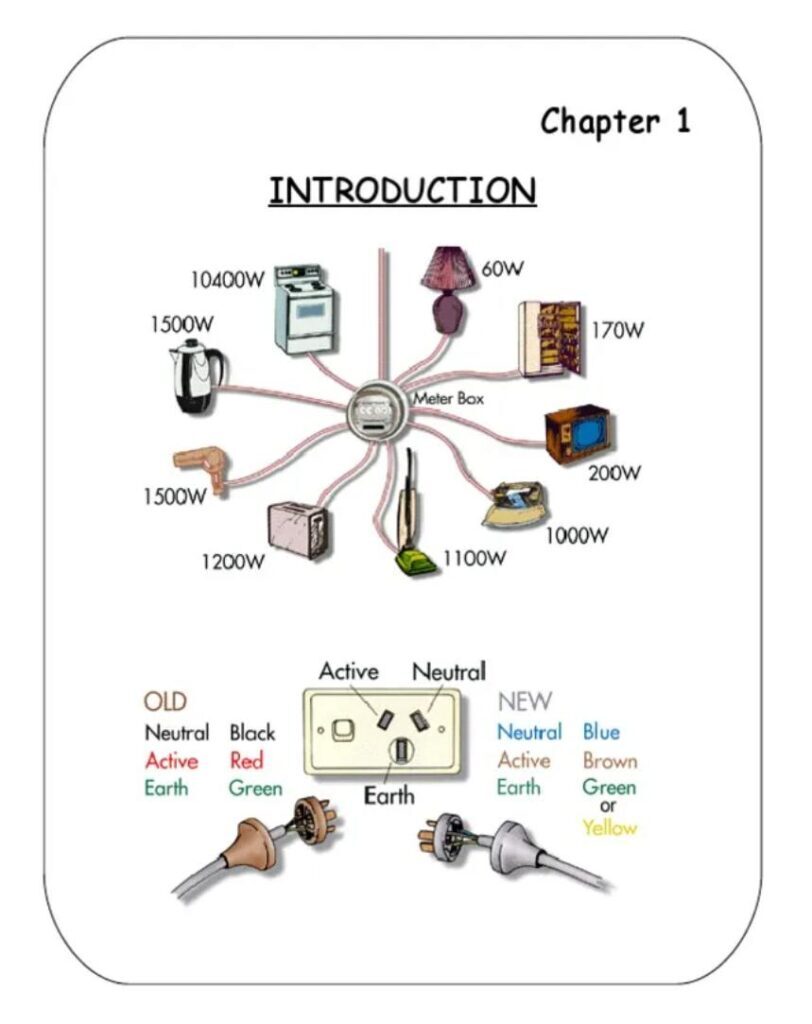

Every site has predictable categories:

- motors

- HVAC systems

- lighting

- production equipment

- IT or telecom loads

- auxiliary systems

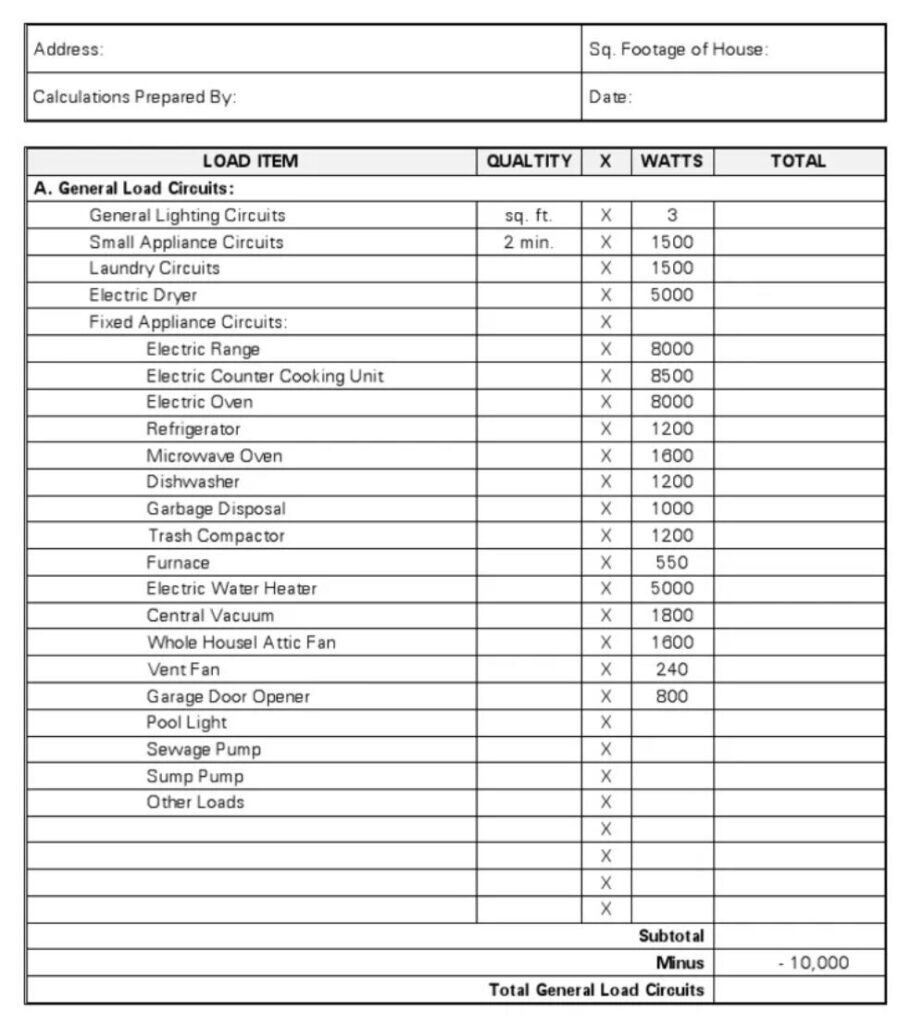

For each item, I care about four things:

- rated power

- quantity

- phase type

- starting method

Nameplate power matters, but it is not enough on its own.

A 30 kW motor is not just “30 kW” to a generator. How it starts matters more than how it runs.

Step 2: Separate Running Load from Starting Load

This is where most mistakes happen.

Running load is what equipment consumes after it reaches steady speed.

Starting load is what it demands for a few seconds during startup.

A motor with direct-on-line starting can draw five to seven times its rated power during startup. Star-delta reduces this, and VFDs reduce it further, but they never eliminate starting impact completely.

In generator sizing, the largest motor often dictates the minimum generator size, even if its running power is not dominant.

If you size only for running load, the generator may start, but voltage dip, frequency drop, or nuisance trips will eventually show up on site.

Step 3: Apply Diversity Carefully, Not Optimistically

Not everything runs at the same time. That’s true.

But diversity is a judgment call, not a default number.

In practice, I use different diversity ranges depending on application:

- industrial sites: typically 0.7–0.85

- commercial buildings: typically 0.6–0.75

- telecom sites: close to 1.0

- data centers: effectively 1.0

What I never do is apply diversity to starting current unless I am absolutely certain motors will never start together. In the real world, that certainty is rare.

Step 4: Convert kW to kVA Conservatively

Generators are rated in kVA, not kW.

If the site power factor is unknown, I assume 0.8.

Not because it’s ideal, but because it’s safe.

Underestimating kVA demand is one of the fastest ways to end up with a generator that looks adequate on paper but struggles under real operating conditions.

Step 5: Add Margin for Reality, Not Comfort

I always add margin, but I don’t add it blindly.

Margins account for:

- future load growth

- temperature and altitude derating

- system aging

- non-linear loads such as UPS systems and VFDs

Typically, this margin falls between 10% and 20%.

More than that usually indicates uncertainty upstream, not good engineering.

A generator that runs consistently below 30% load is not “safe”.

It is inefficient, prone to wet stacking, and often a sign that the original load calculation lacked confidence.

What Most People Get Wrong When Calculating Site Load

A correct site load calculation is not the sum of equipment ratings.

It is the maximum realistic electrical stress the system will experience, including motor starts and future expansion.

If you size for averages, you will eventually pay for peaks.

When Oversizing Is Not the Answer

Bigger is not always better.

For lightly loaded standby systems, rental fleets, emission-regulated markets, or sites planning future parallel operation, oversizing creates its own problems.

In these cases, splitting loads, using soft starters, or designing for parallel generators often produces a more reliable and more economical result than simply choosing a larger unit.

How This Works in Real Projects

In real projects, I rarely rely on a single formula.

Once I understand:

- the load categories

- the largest motor and its starting behavior

- the application type

- whether the generator is intended for prime or standby operation

the correct generator size usually becomes clear.

At that point, the calculation is no longer theoretical.

It reflects how the site will actually behave when the power is needed most.