I’ve supplied diesel generator sets for years, and kW vs kVA confusion is still one of the most common reasons buyers choose the wrong generator.

Not because the formulas are hard—but because most people don’t realize which number actually matters for their load.

This article explains it the way we deal with it in real export and configuration projects, not the way it’s usually explained online.

A diesel generator’s real output is kW, not kVA.

kVA is a sizing reference - your load decides whether the generator survives long-term.

If you remember only one sentence, remember this one.

What kW and kVA really mean in practice

kW - the power your equipment actually uses

kW (kilowatt) is real power.

This is the power your loads actually consume to do work.

In real projects, when a buyer tells me:

- “Our load is about 180 kW”

- “The site consumes around 120 kW continuously”

That is usable information.

Motors, compressors, heaters, servers, and production equipment all run on kW, not kVA.

kVA - the generator’s electrical capacity

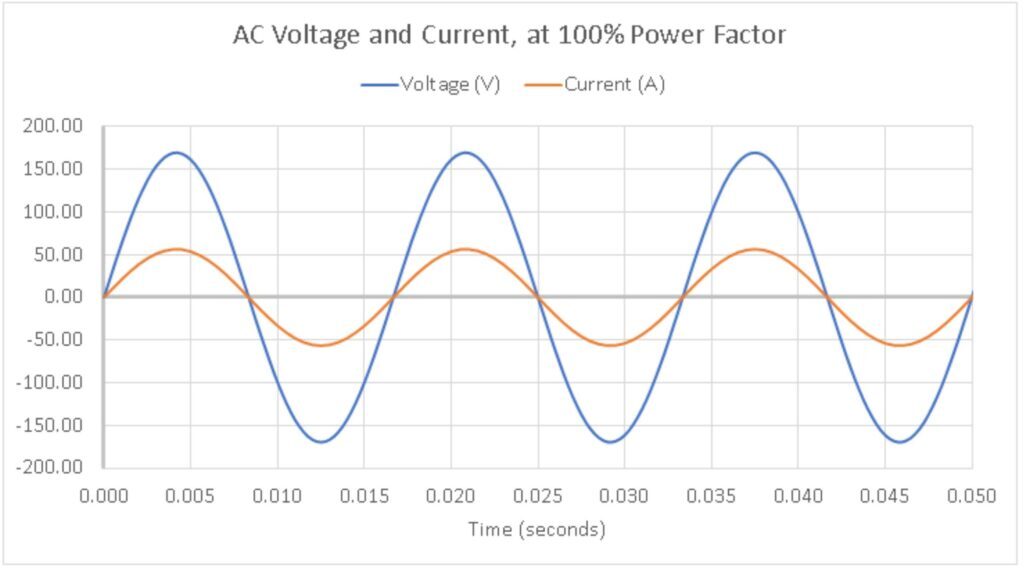

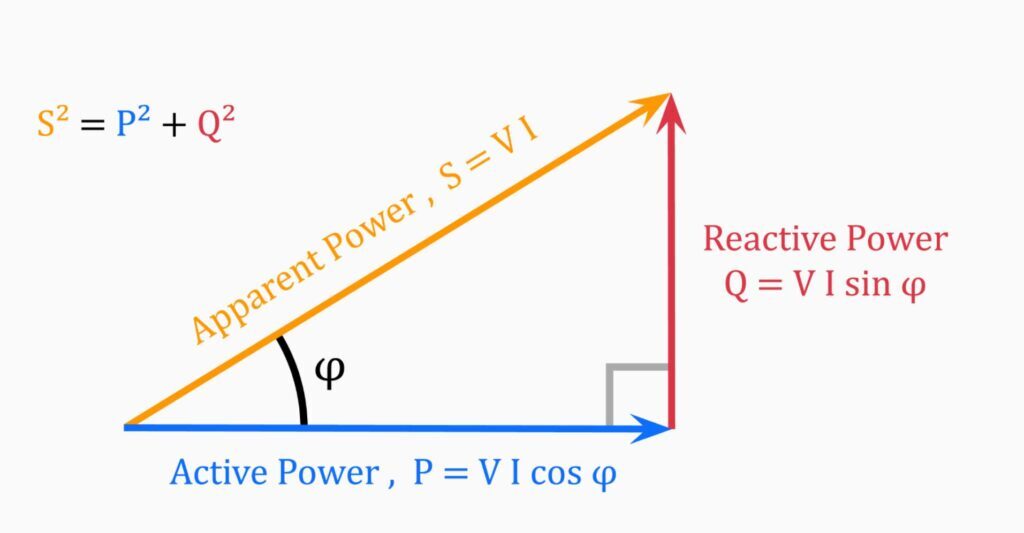

kVA (kilovolt-ampere) is apparent power.

It reflects how much electrical load the alternator can carry, including inefficiencies caused by inductive loads.

kVA mainly affects:

- Alternator sizing

- Cable and breaker selection

- Nameplate ratings

But your equipment does not consume kVA.

The bridge between them: Power Factor (PF)

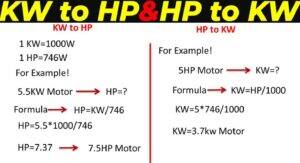

kW and kVA are connected by power factor.

kW = kVA × Power Factor

kVA = kW ÷ Power Factor

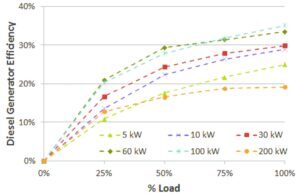

In most industrial diesel generator applications:

- Power Factor = 0.8

This isn’t theoretical—it reflects how real industrial loads behave.

Why generators are usually rated at 0.8 PF

That’s why you often see ratings like:

| Generator Rating | Usable Power |

|---|---|

| 100 kVA | 80 kW |

| 125 kVA | 100 kW |

| 250 kVA | 200 kW |

| 500 kVA | 400 kW |

So when you see 250 kVA / 200 kW, it’s the same generator, just expressed two ways.

The most common mistake buyers make

Mistake #1: Choosing based on kVA only

Many buyers say:

“I need a 250 kVA generator.”

But when I ask:

- What’s the actual load in kW?

- Is it standby or prime power?

- Are there large motors or compressors?

They often don’t know.

This is where problems start.

A generator can look fine in kVA but still be overloaded in kW, especially in continuous operation.

Mistake #2: Ignoring load behavior

Two sites with the same kW demand can behave very differently.

In real export projects, I’ve seen:

- Printing factories overload generators due to motor starting current

- Telecom sites trip generators despite low average kW

- Workshops underestimate reactive power from old motors

kVA alone doesn’t protect you from poor load behavior.

Prime power vs standby power (this matters more than most people think)

Standby Power (ESP)

- Used only during outages

- Can run near rated kW

- Not designed for continuous operation

Prime Power (PRP)

- Runs long hours or 24/7

- Must be derated in real projects

- Requires kW margin for engine life

If you run a standby-rated generator as prime power, failure is a matter of time, not luck.

How I actually size generators in real projects

This is the framework I use in practice:

- Start with actual load in kW

- Confirm:

- Standby or prime operation

- Motor-heavy or resistive load

- Add a safety margin (usually 10–25%)

- Convert to kVA after kW is confirmed

Not the other way around.

When kVA really becomes critical

There are situations where kVA deserves more attention:

- Very low power factor loads

- Poor site electrical design

- Large motor starting without soft starters

- Parallel generator systems

But if you’re asking “kW vs kVA?”, your first mistake is almost always on the kW side.

Conclusion

kW determines whether your generator survives.

kVA only tells you how big the alternator is.

If you want one number to be right when choosing a diesel generator,

make sure it’s the kW.